Exercise is defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “a subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective”.

The benefits of exercise refer to the various ways that exercise contributes to overall health and well-being. While specific benefits can vary depending upon the nature and intensity of the exercise, they generally include physical improvements such as enhanced fitness and strength, as well as mental advantages like improved mood and cognitive function.

One main physical benefit of exercise is the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness and performance. It can help manage or prevent chronic diseases, strengthen muscles and bones, and even extend lifespan.

Exercise has also a powerful impact on our mental health and mood. By engaging in regular physical activity, we can decrease the risk of depression, improve sleep quality, and enhance our overall mood and well-being.

As a result, questions arise regarding how much exercise should you do per day, the benefits of exercising in the morning, the social benefits of exercise, and the benefits of exercising in the evening. In this article, we will evaluate the 15 health benefits of exercising listed below.

- Helps control obesity

- Prevents metabolic syndrome

- Improves insulin sensitivity

- Prevents type 2 diabetes

- Protects against cardiovascular diseases

- Protects against coronary heart disease

- Helps control hypertension

- Protects against stroke

- Protects against osteoporosis

- Helps mitigate osteoarthritis

- Improves balance

- Helps reduce pain

- Improves cognitive function

- Helps against depression and anxiety

- Protects against cancer

1. Helps Control Obesity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), obesity in adults is classified by Body Mass Index (BMI), with overweight defined as a BMI of 25.0–29.9, Class I obesity as a BMI of 30.0–34.9, Class II obesity as a BMI of 35.0–39.9, and Class III obesity (also known as severe or extreme obesity) as a BMI greater than 40.0.

Controlling obesity primarily involves maintaining a balance between caloric intake and physical activity to prevent a positive caloric balance. This could be achieved through changes in diet and an increase in physical activity, preferably to moderate levels.

Regular exercise helps in controlling obesity by burning calories, which helps in maintaining a balance between caloric intake and expenditure. It is particularly effective in reducing visceral adipose tissue, which is associated with higher health risks.

The amount of exercise needed for controlling obesity can vary. However, a 2010 study by I-Min Lee from Brigham and Women’s Hospital has shown that a threshold of about 60 minutes a day of moderate-intensity activity is needed to prevent significant weight gain. Lower levels of activity can prevent further gains in visceral adipose tissue, while higher levels can decrease it.

The benefits of exercise in controlling obesity will last as long as the physical activity is maintained. If physical activity levels decrease, the benefits may also decrease.

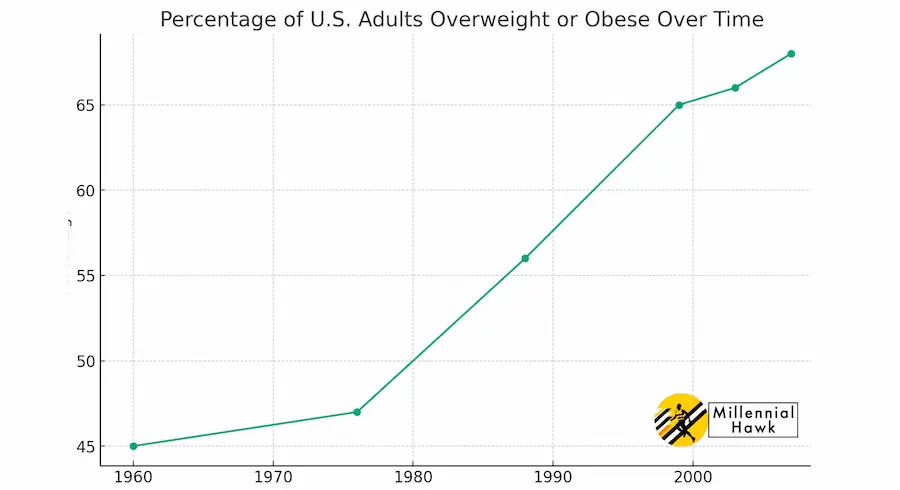

This graph shows the percentage of the U.S. adult population that was overweight or obese during different years.

2. Prevents Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome, based on the 2009 study by Kurt George Matthew Mayer Alberti, is defined as a cluster of at least three out of five risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

These risk factors tend to co-occur in the same individual and include elevated triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, high blood pressure, elevated fasting glucose, and increased waist circumference.

Exercise helps to prevent metabolic syndrome (MS) for several reasons, according to the 2009 Joint Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association.

- Counteracting Inactivity: Physical inactivity is a primary cause of every major risk factor for metabolic syndrome, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, visceral obesity, prothrombosis, and pro-inflammatory events. Regular physical activity, therefore, directly counters these risk factors.

- Reducing Inflammation and Improving Metabolism: Physical inactivity is associated with low-grade inflammation and impaired metabolism, both of which contribute to MS. Regular physical activity reduces inflammatory markers such as resting C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha concentration. It also improves metabolism.

- Muscle Secretome or Myokines: The muscle secretome, or myokines, are substances secreted by muscles during exercise. These myokines have been hypothesized to mediate some of the health benefits of regular exercise, particularly in chronic diseases associated with low-grade inflammation and impaired metabolism. For instance, contracting skeletal muscle during exercise produces IL-6, which has anti-inflammatory properties.

- Reduction of Sedentary Time: Physical activity, even light daily exercise, reduces total sedentary time. This is particularly beneficial for older individuals, as it has been suggested that people over 60 years old may benefit from reducing total sedentary time and increasing the number of light physical activity bouts during sedentary periods.

3. Improves Insulin Sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity refers to how effectively the body’s cells respond to insulin. An individual with high insulin sensitivity would require less insulin to lower blood glucose levels than someone with lower insulin sensitivity.

According to a 1985 study by R Burstein from McGill University Montreal, peripheral tissue glucose disposal dropped from 15.6 to 10.1 to 8.5 ml/kg/min, 12, 60, and 168 hrs after the last exercise bout, respectively, compared to 7.8 ml/kg/min in sedentary people.

Improving insulin sensitivity means enhancing the body’s cells’ response to insulin. This can be quantified by an increase in the rate of glucose disposal. For example, seven days of aerobic training increases whole-body insulin sensitivity in 22- and 58-year-old men and women, according to East Carolina University.

Exercise improves insulin sensitivity by increasing the uptake of glucose into skeletal muscle and by promoting the translocation of GLUT4, a glucose transporter, from intracellular locations to the plasma membrane.

When asking how much exercise is necessary to improve insulin sensitivity, we can point to a study titled “Effects of exercise and lack of exercise on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity” which found that even a single bout of muscle contraction increased insulin sensitivity in healthy individuals.

However, more significant increases in whole-body insulin sensitivity were observed after seven days of aerobic training.

The benefits of exercise on insulin sensitivity can last for a few hours to a couple of days, but without regular exercise, these improvements may decrease over time.

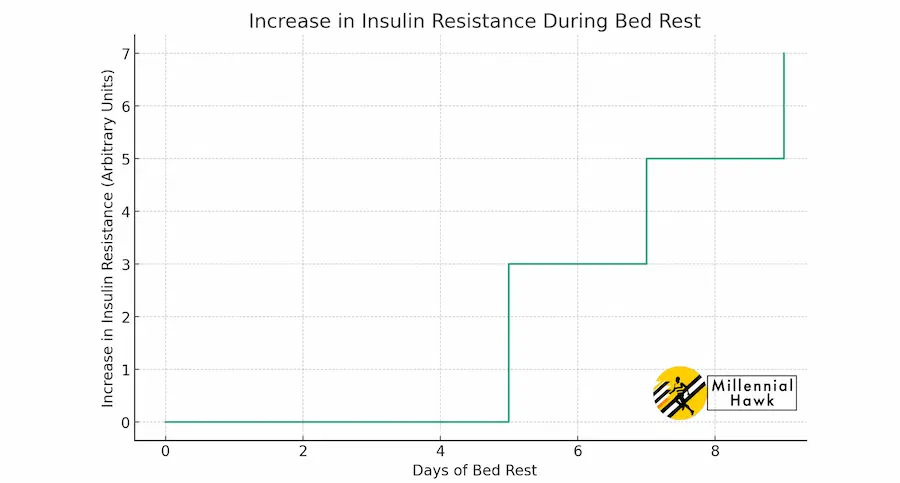

For instance, even in individuals who are highly trained in endurance sports, insulin sensitivity levels return to those of sedentary individuals after 38 to 60 hours of not exercising, as reported by Nagoya University. This graph shows an increase in insulin resistance over time during periods of bed rest.

4. Prevents Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 Diabetes is a chronic condition that affects the way your body metabolizes sugar (glucose), an important source of fuel for your body. With type 2 diabetes, your body either resists the effects of insulin — a hormone that regulates the movement of sugar into your cells — or doesn’t produce enough insulin to maintain normal glucose levels.

There are numerous studies that have demonstrated the benefits of physical activity in preventing type 2 diabetes. A randomized clinical trial from China-Japan Friendship Hospital showed that prescribed exercise resulted in a 46% reduction in the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance.

In the Finnish DPS study, it was found that subjects who did not reach their weight loss goals but met the goal for exercise volume (more than four hours per week) were 80% less likely to develop Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) compared to the reference group.

In a 2006 study conducted by Richard F Hamman from George Washington University, individuals who achieved a physical activity goal of more than 150 minutes per week but did not meet a weight loss goal still had a 44% reduction in diabetes incidence. Thus, regular physical activity is recognized as a crucial measure in preventing type 2 diabetes. This video from CNN explains the benefits of exercise for type 2 diabetes.

Exercise improves glucose sensitivity and mechanisms that directly affect endothelial metabolism, which can aid in preventing the development of type 2 diabetes. Regular physical activity can also decrease fat-to-lean mass ratio and visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio, both of which are beneficial for individuals with a BMI between 25 and 30.

While the specific amount of exercise needed for this benefit can vary between individuals, Dr. Hamman suggests that individuals who achieve a goal of more than 150 minutes of physical activity per week can reduce their incidence of diabetes by 44%.

5. Protects Against Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) refers to all diseases that affect the heart and blood vessels. The American Heart Association lists major CVDs as including subclinical atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, acute coronary syndrome (myocardial ischemia), angina pectoris, stroke (cerebrovascular disease), high blood pressure, congenital cardiovascular defects, cardiomyopathy and heart failure, among other less prevalent conditions.

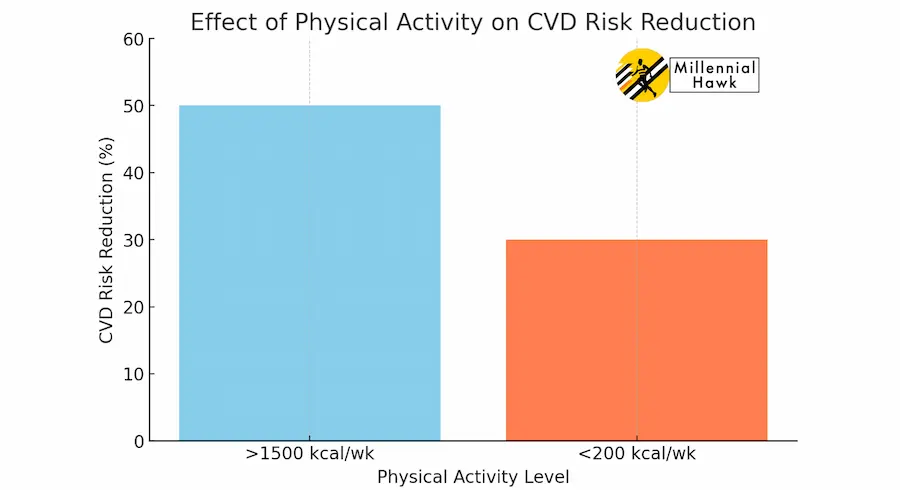

A study conducted by Samia Mora from Brigham and Women’s Hospital found that physical activity can reduce CVD risk by 30% to 50%. Dr. Mora compared 27,000 women who engaged in >1500 kcal/wk of physical activity with those who engaged in <200 kcal/wk, as illustrated in this graph.

The analysis revealed that the inverse relationship between higher levels of physical activity and fewer CVD events could be attributed to “known” risk factors, which accounted for 59.0% of CVD and 36% of coronary heart disease (CHD) cases. This graph shows

6. Protects Against Coronary Heart Disease

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a disease of the heart and coronary arteries characterized by atherosclerotic arterial deposits that block blood flow to the heart, leading to myocardial infarction, or heart attack.

According to a 2010 study by Fernando Ribeiro from the University of Porto, exercise can contribute to the primary prevention of CHD through several mechanisms: it increases nitric oxide and antioxidants, reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in the blood by decreasing production from various tissues, and enhances the regenerative capacity of the endothelium by increasing the number of circulating endothelial precursor cells.

Other studies have shown the benefits of physical activity in preventing CHD. A 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Report suggests that unfit individuals who improved their fitness status had a 35% lower mortality risk.

Furthermore, the American Heart Association recognized physical inactivity as a risk factor for CHD and CVD in 1992, and the Surgeon General concluded in 1996 that “regular physical activity or cardiorespiratory fitness decreases the risk of CVD and CHD”. This evidence underscores the importance of regular physical activity in preventing CHD.

The specific amount of exercise needed can vary. However, a 2010 study by Peter Kokkinos from Veterans Affairs Medical Center noted that a 1-MET decrease in maximal aerobic exercise capacity increases the mortality risk by 12%.

Those who achieved greater than 9 METs in maximal aerobic exercise capacity had a 61% lower mortality risk, suggesting that higher levels of physical activity are associated with a lower risk of CHD.

7. Helps Control Hypertension

Hypertension is a medical condition characterized by high blood pressure. Specifically, it is defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) equal to or greater than 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) equal to or greater than 90 mmHg. It can also be defined as taking antihypertensive medication.

According to the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Report, more than 62% of adults in the United States have blood pressure above optimal levels. Additionally, the National Physical Activity Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction (NPAGCR) concluded that both aerobic and progressive resistance exercise result in reduced SBP and DBP in adult humans.

Helping control hypertension refers to actions or interventions that reduce or maintain blood pressure levels within a healthy range. This typically involves lifestyle changes such as increasing physical activity levels, dietary changes, and medication.

Exercise helps control hypertension by inducing post-exercise hypotension, a decrease in blood pressure after exercise. According to a 2010 study by John D Eicher from the University of Connecticut, potential mechanisms for post-exercise hypotension involve the renin-angiotensin system and sympathetic nervous systems and include modulation by cardiometabolic, inflammatory, and hemostatic factors.

When asking how much exercise you need to control hypertension, we can point to research published in the American Heart Journal, which suggests a dose-response relationship between the intensity of physical activity and the lowering of blood pressure post-exercise.

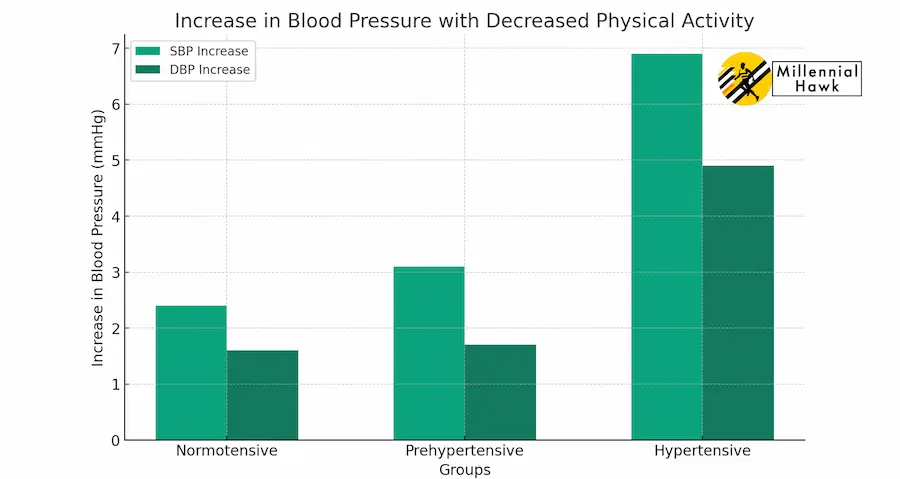

For each 10% increase in relative VO2peak, SBP decreased 1.5 mmHg and DBP 0.6 mmHg. This graph shows the increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure with decreased physical activity for normotensive, prehypertensive, and hypertensive subjects.

8. Protects Against Stroke

A stroke is a sudden diminution or loss of consciousness, sensation, and voluntary motion caused by a rupture or obstruction (such as by a clot) of a blood vessel in the brain.

According to the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, each year, approximately 800,000 individuals experience stroke, with around 185,000 deaths in the U.S.

The most physically active men and women have a 25% to 30% lower risk of stroke incidence and mortality. Engaging in exercise can lower the risk of stroke. Moderate physical activity can cause an 11% reduction in the risk of stroke, and high physical activity can cause a 19% reduction.

A 2009 meta-analysis by Carl D Reimers from Zentralklinik Bad Berka, incorporating 33 prospective cohort studies and 10 case-control studies, found that physical activity reduces the relative risk of fatal or non-fatal cerebral infarction to 0.75, while the corresponding relative risks for cerebral hemorrhage and stroke of unspecified type are 0.67 and 0.71, respectively.

Potential mechanisms of risk reduction by physical activity on stroke include an antihypertensive effect, a beneficial effect on lipid metabolism, and improved endothelial function (increased endothelial NOS activity and extracellular superoxide dismutase expression).

Other mechanisms may include lowered blood viscosity, reduced tendency toward platelet aggregation, increased fibrinolysis, reduced plasma fibrinogen, increased activity of plasma tissue plasminogen activator activity, and higher levels of HDL-cholesterol.

The exact amount of exercise needed can vary, but research indicates that moderate to high levels of physical activity can lead to significant reductions in stroke risk.

9. Protects Against Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a decrease in bone mass that results in a decrease in density and enlargement of bone spaces, which produces porosity and brittleness. Interventions, such as exercise, can prevent or reduce bone mass loss, which decreases the likelihood of developing osteoporosis.

Exercise protects against osteoporosis by applying gravitational and muscle contraction forces on the skeleton, which can prevent or reverse about 1% of bone loss per year in the lumbar spine and femoral neck in both pre- and postmenopausal women.

The benefits of exercise on osteoporosis come from research on a variety of populations, including a 2010 study by Joan Vernikos, former director of NASA’s Life Sciences Division, on cosmonauts who spent up to 7 months in space, showing a loss of about 1-1.6% of bone mineral density.

Research on spinal cord injury patients also showed significant reductions in bone mineral content and density in the legs and pelvis when compared to their non-injured twins. A 1999 study from Vrije Universiteit also shows a yearly loss of around 1% of bone density in sedentary pre- and postmenopausal women.

10. Helps Mitigate Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a condition involving the degeneration of cartilage and its underlying bone within a joint. The evidence that exercise affects osteoarthritis comes from a collection of studies that look at different types of physical activities and their impact on joint health.

A set of activities that have been associated with an increased prevalence of incident osteoarthritis are illustrated in this graph, including certain sports and strenuous physical activities.

The mechanism of how exercise assists in mitigating osteoarthritis involves its ability to strengthen the muscles around the joint, improving flexibility and potentially reducing pain. Exercise can help manage body weight, which can ease pressure on joints, and can also promote better joint health through improved circulation and inflammation control.

The amount of exercise needed for benefit against osteoarthritis could vary, but according to NPAGCR, regular moderate to vigorous physical activity of 30–60 minutes can provide general health benefits without increasing the risk of developing osteoarthritis in individuals without pre-existing major joint injury.

The benefits can last as long as the person continues to regularly exercise. If exercise is discontinued, the benefits may gradually decrease over time. As osteoarthritis is a long-term, progressive condition, consistent and ongoing physical activity is key to managing symptoms and potentially slowing progression.

11. Improves Balance

Balance is the ability to maintain the center of gravity for the body within the base of support, producing minimal postural sway. Balance problems can occur from the lack of usage of the nervous system controlling skeletal muscle movement against gravity.

Exercise helps to improve balance by strengthening the muscles and training the nervous system. Regular exercise against gravity helps the nervous system in regulating muscle movement and enhances coordination, resulting in improved balance.

Joan Vernikos has conducted research indicating that exercise improves balance. This conclusion is based on studies of astronauts, who display accelerated balance problems upon returning to Earth after as little as 9 days in space. These issues are believed to result from inappropriate neurovestibular responses caused by insufficient exercise against gravity.

The NPAGCR found strong evidence that physical activity programs that emphasize both balance training and muscle strengthening can reduce the risk of falls in old Americans.

The amount of exercise needed to improve balance varies, but according to the NPAGCR, achieving a minimum of 9 to 14.9 MET-hours per week of physical activity can significantly reduce the risk of bone fracture. This translates to more than 4 hours per week of walking or similar weight-bearing exercises that place stress on the bones.

12. Helps Reduce Pain

Pain is a basic bodily sensation that is induced by a noxious stimulus, received by free nerve endings, and characterized by physical discomfort. A 2010 study by Benjamin W. Friedman from Albert Einstein College of Medicine suggests that one-quarter of adults have at least 1 day of low back pain in a 3-month period and most adults suffer low back pain at some point during their lives.

Well-trained individuals seem to exhibit higher pain tolerance to skeletal muscle biopsies and to skin suturing, but clinical trials are still required to verify this observation.

Exercise can help to reduce pain through moderate-intensity aerobic exercise reducing cutaneous and deep tissue hyperalgesia induced by acidic saline and also stimulating the synthesis of neurotrophic factor-3 in some muscles. However, these results are still limited to animal models and cannot be generalized to chronic pain syndromes in humans.

Exercise training is a long-suggested method to reduce pain, but it’s not a cure for the source of the pain. Moreover, the available evidence, according to various clinical trials, is still somewhat constrained.

The actual amount of exercise needed to achieve the benefit of pain reduction, as well as the specific exercises that are effective, remain unclear and require further research to identify the optimal dose-response relationships regarding exercise and pain reduction, especially for low back pain.

13. Improves Cognitive Function

Cognitive function is an intellectual process by which one becomes aware of, perceives, or comprehends ideas. It involves all aspects of perception, thinking, reasoning, and remembering.

There is extensive research showing the positive effects of exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, on cognitive function across different age groups, from children to older adults. Regular physical activity and higher levels of fitness have been linked to better cognitive function and a lower risk of cognitive decline.

As per a 2008 study by Charles H. Hillman from the University of Illinois, exercise can improve cognitive function through several mechanisms. It has been linked to structural changes in the brain, such as increased volume in certain regions and increased neurogenesis. Exercise can also induce the expression of certain growth factors that protect the brain. Changes in blood flow and electrical function in the brain have also been associated with exercise.

The specific amount of exercise needed to improve cognitive function can vary. A 2001 study by Kristine Yaffe from the University of California has shown that every 10 blocks walked per day in women over 65 years old resulted in a 13% less impairment in cognitive function.

A 2004 study by Jennifer Weuve from Harvard School of Public Health involving 18,000 women aged 71-80 years old found that higher levels of regular physical activity were strongly associated with higher levels of cognitive function and a 20% lower risk of cognitive impairment. This video from the University of California explains the impact of exercise on cognitive functioning.

14. Helps Against Depression and Anxiety

Depression is a mood disorder marked by sadness, inactivity, difficulty with thinking and concentration, a significant increase or decrease in appetite and time spent sleeping, feelings of dejection, hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal thoughts or an attempt to commit suicide.

Anxiety is an abnormal and overwhelming sense of apprehension and fear, often marked by physiological signs such as sweating, tension, an increased pulse, doubt concerning the reality and nature of the threat, and self-doubt about one’s capacity to cope with it.

The 2008 NPAGCR found that active individuals were 45% less likely to experience depressive symptoms compared to inactive individuals.

In a closer analysis of 28 cohorts, it was discovered that nearly 4 years of physical inactivity increased the risk of depression by 49% without adjusting for other risk factors, and by 22% after adjusting for factors such as age, sex, race, education, income, smoking, alcohol use, and chronic health conditions.

According to a 2005 study by Andrea L Dunn titled “Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose-response,” a recommended exercise dose against depression and anxiety is about 12 miles/week of walking for 12 weeks which reduced depressive symptoms by 47% from baseline.

A 2001 study from Freie Universitaet showed the relatively quick effect of exercise involving 10 days of walking for 30 minutes/day also showed a decrease in the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and self-assessed intensity of symptoms.

To maintain the benefits, ongoing exercise is needed. The duration of the beneficial effects of exercise can significantly vary among individuals, with some feeling the benefits immediately, while others may require longer periods of continuous activity. Ceasing to continue physical activity after experiencing benefits could potentially lead to the return of depression and anxiety symptoms.

15. Protects Against Cancer

Cancer is defined as a malignant tumor of potentially unlimited growth that expands locally by invasion and systemically by metastasis. Protecting against cancer refers to interventions or activities that can decrease the prevalence or risk of developing certain types of cancer. This typically involves lifestyle changes, such as increased physical activity.

The proof that exercise affects cancer comes from a range of research studies, focusing on varying types of cancer. A 1997 study from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School has shown that physical inactivity increases the prevalence of some site-specific cancers such as colon, breast, and endometrial cancers.

For colon cancer, exercise might reduce fecal transit time, lowering exposure to fecal carcinogens, decrease blood insulin levels, increase anti-inflammatory myokines, and decrease body fat. For breast cancer, physical activity might impact BMI, hormone levels, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Exercise can also enhance cellular mechanisms that promote cell apoptosis and reduce proliferation in breast cells.

How Much Exercise Should You Do Per Day?

It is recommended that children and adolescents aged 5-17 engage in at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity each day.

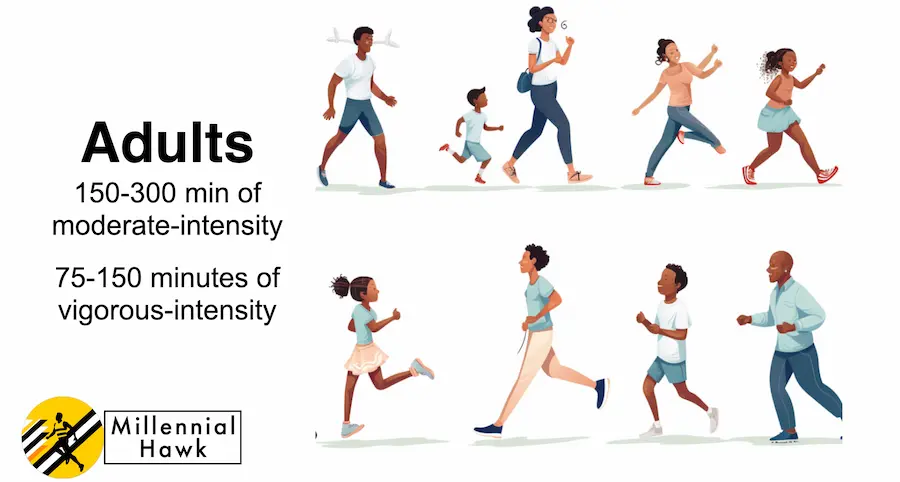

Adults aged 18–64 should aim for at least 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, or at least 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, which is equivalent to 22-43 minutes of moderate-intensity or 11-21 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per day, as illustrated in this graph.

What Are The Benefits of Exercise In The Morning?

The benefits of exercising in the morning are listed below.

- Morning exercise can help regulate your body’s internal clock or circadian rhythm.

- Exercising in the morning, especially in a fasted state, can stimulate greater fat oxidation.

- Morning exercise is associated with improved weight ma

- Morning workouts can influence eating behaviors, possibly leading to a reduction in fat and carbohydrate intake throughout the day.

Can Exercise Reduce Social Isolation?

Yes, exercise, particularly when conducted in a group setting like team sports, can help reduce social isolation. This is backed by a 2013 study from Victoria University indicating various psychological and social health benefits associated with participation in sports activities by children and adolescents. The most commonly reported benefits include improved self-esteem and enhanced social interaction, which can inherently reduce feelings of isolation.

What Are The Benefits of Exercise In The Evening?

The benefits of exercising in the evening are shown below.

- Exercising in the evening serves as a stress reliever after a long day.

- Exercise in the evening may have a positive impact on sleep quality.

- Walking in the evening experienced greater decreases in fat mass compared to those exercising in the morning.

What Happens When You Exercise Too Much?

When you exercise too much, the condition known as overtraining can occur, which is characterized by symptoms like hormonal imbalances, immune system suppression, muscle damage, and decreased performance. The identification of overtraining is complex and requires monitoring multiple parameters, such as neuroendocrine levels and muscle glycogen reserves, to distinguish it from the short-term fatigue associated with regular intense training.